“The Past, Present, and Future of Local Storage for Web Applications”

ersistent local storage is one of the areas where native client applications have held an advantage over web applications. For native applications, the operating system typically provides an abstraction layer for storing and retrieving application-specific data like preferences or runtime state. These values may be stored in the registry, INI files, XML files, or some other place according to platform convention. If your native client application needs local storage beyond key/value pairs, you can embed your own database, invent your own file format, or any number of other solutions.

What we really want is

- a lot of storage space

- on the client

- that persists beyond a page refresh

- and isn’t transmitted to the server

Before HTML5, all attempts to achieve this were ultimately unsatisfactory in different ways.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF LOCAL STORAGE HACKS BEFORE HTML5

In the beginning, there was only Internet Explorer. Or at least, that’s what Microsoft wanted the world to think. To that end, as part of the First Great Browser Wars, Microsoft invented a great many things and included them in their browser-to-end-all-browser-wars, Internet Explorer. One of these things was called DHTML Behaviors, and one of these behaviors was called userData. As you survey these solutions, a pattern emerges: all of them are either specific to a single browser, or reliant on a third-party plugin. Despite heroic efforts to paper over the differences (in dojox.storage), they all expose radically different interfaces, have different storage limitations, and present different user experiences. So this is the problem that HTML5 set out to solve: to provide a standardized API, implemented natively and consistently in multiple browsers, without having to rely on third-party plugins.

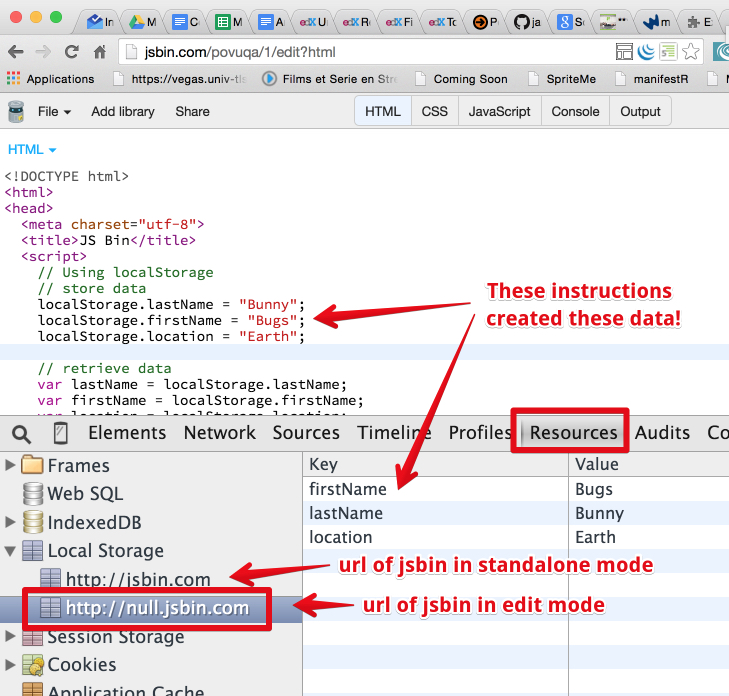

USING HTML5 STORAGE

HTML5 Storage is based on named key/value pairs. You store data based on a named key, then you can retrieve that data with the same key. The named key is a string. The data can be any type supported by JavaScript, including strings, Booleans, integers, or floats. However, the data is actually stored as a string. If you are storing and retrieving anything other than strings, you will need to use functions like parseInt() or parseFloat() to coerce your retrieved data into the expected JavaScript datatype.

-

TRACKING CHANGES TO THE HTML5 STORAGE AREA The storage event is supported everywhere the localStorage object is supported, which includes Internet Explorer 8. IE 8 does not support the W3C standard addEventListener (although that will finally be added in IE 9). Therefore, to hook the storage event, you’ll need to check which event mechanism the browser supports. (If you’ve done this before with other events, you can skip to the end of this section. Trapping the storage event works the same as every other event you’ve ever trapped. If you prefer to use jQuery or some other JavaScript library to register your event handlers, you can do that with the storage event, too.)

-

LIMITATIONS IN CURRENT BROWSERS “5 megabytes” is how much storage space each origin gets by default. This is surprisingly consistent across browsers, although it is phrased as no more than a suggestion in the HTML5 Storage specification. One thing to keep in mind is that you’re storing strings, not data in its original format. If you’re storing a lot of integers or floats, the difference in representation can really add up. Each digit in that float is being stored as a character, not in the usual representation of a floating point number.

BEYOND NAMED KEY-VALUE PAIRS: COMPETING VISIONS

While the past is littered with hacks and workarounds, the present condition of HTML5 Storage is surprisingly rosy. A new API has been standardized and implemented across all major browsers, platforms, and devices. As a web developer, that’s just not something you see every day, is it? But there is more to life than “5 megabytes of named key/value pairs,” and the future of persistent local storage is… how shall I put it… well, there are competing visions.

One vision is an acronym that you probably know already: SQL. In 2007, Google launched Gears, an open source cross-browser plugin which included an embedded database based on SQLite. This early prototype later influenced the creation of the Web SQL Database specification. Web SQL Database (formerly known as “WebDB”) provides a thin wrapper around a SQL database, allowing you to do things like this from JavaScript